The Rice Sack and the Marshall Plan

The Episode

Welcome to this episode of “Now & Then at Dodona Manor.” In this video, we’re going to talk about what some consider the greatest act of foreign policy in American history: the Marshall Plan. For most people, learning about the Marshall Plan was the first time that they heard George Marshall’s name and discovered his unique position as a soldier-statesman. This episode is going to dive into the plan itself, but it will also give you a sense of Marshall’s thoughts and personality as one of the world’s foremost diplomatic leaders.

Questions for Thought and Discussion

A Marshall Plan poster representing all the countries who participated in the plan

After Marshall’s return from his mission as special envoy to China, President Harry Truman appointed him Secretary of State. Marshall was swiftly and unanimously confirmed by the Senate, taking the oath of office in the White House on January 21, 1947. Immediately after assuming duties as Secretary of State, Marshall devoted much of his time to prepare for a meeting of the Council of Foreign Ministers (of Great Britain, France, the Soviet Union and the United States). This meeting was to decide the future of Germany and Eastern Europe and gave Marshall a unique understanding of the drastic postwar plight of Europe, influencing what would later become the Marshall Plan itself.

After Marshall’s return from his mission as special envoy to China, President Harry Truman appointed him Secretary of State. Marshall was swiftly and unanimously confirmed by the Senate, taking the oath of office in the White House on January 21, 1947. Immediately after assuming duties as Secretary of State, Marshall devoted much of his time to prepare for a meeting of the Council of Foreign Ministers (of Great Britain, France the Soviet Union and the United States). This meeting was to decide the future of Germany and Eastern Europe and gave Marshall a unique understanding of the drastic postwar plight of Europe, influencing what would later become the Marshall Plan itself.

What was this great plan that most of us learned about in school? The Marshall Plan was officially called the Economic Recovery Program, or as it said on the bill signed by President Truman in 1948, “An act to promote world peace and the general welfare, national interest, and foreign policy of the United States through economic, financial, and other measures necessary to the maintenance of conditions abroad in which free institutions may survive and consistent with the maintenance of the strength and stability of the United States.” Man, what a mouthful! Luckily that’s just the name on the bill, but before the ERP even had a name, it was proposed in an address at Harvard University by Secretary of State Marshall.

Marshall decided in June 1947 to accept an honorary degree from Harvard University. The State Department informed the president of the Harvard alumni association that Marshall would make a speech at its afternoon meeting, but Marshall made it clear that he did not want it to be a keynote address. Representatives from other governments, reporters, the public, and not even the president of Harvard himself could have known the groundbreaking speech that would ensue.

Marshall with J. Robert Oppenheimer, James Bryant Conant, Omar Bradley, and T. S. Eliot before his speech

When the day of the speech came, a crowd of 15,000 did not expect to see history made in Harvard Yard, but simply to admire one of America’s most beloved public servants. However, everyone who heard the speech sensed that the intentional remarks on the political and economic crisis in Europe marked a momentous event. In his speech, Marshall told of the disastrous social and economic conditions in Europe and expressed the need for economic aid to rebuild the devastated nations of Europe and to ensure that democracy was saved following the destruction of World War II. When Marshall said, “It is logical that the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace,” the Secretary of State committed the United States to consider a plan that would be uniquely in the hands of Europeans for its creation. Marshall added, “Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation and chaos. Its purpose should be the revival of a working economy in the world so as to permit the emergence of political and social conditions in which free institutions can exist.”

Marshall at Harvard, 1947

British Foreign Minister Ernest Bevin heard a BBC report about Marshall’s speech that evening shortly after it was given; the next day he contacted French Foreign Minister Georges Bidault, and they began immediately to organize a June 17 conference in Paris to consider the ideas Marshall had outlined. The key task was to define the scope of the economic problem in Europe, what Europeans could do about it, and what was needed from the United States. Many in Congress were concerned about communist uprisings in Europe and skeptical about any U.S. government-backed welfare programs. The Europeans wanted to know what the United States required of Europe, and the Americans wanted the potential aid recipients to list their resources for self-help. Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov was invited to the Paris meetings, and some countries in the Soviet sphere of influence, such as Poland and Czechoslovakia, expressed an interest in participating. Molotov walked out on July 2, however, labeling the Marshall Plan American economic imperialism; Soviet-dominated countries followed him out.

Thanks to Marshall’s unquestioned trustworthiness and tireless efforts to campaign for the plan, the Republican-led U.S. Congress passed the ERP, authorizing $13 billion in aid to be sent to Europe over four years. Marshall later said of his efforts to push the legislation through Congress: “I traveled all over the country…I worked on that as hard as though I was running for the Senate or the presidency. That’s what I’m proud of…because I had foreigners, I had tobacco people, cotton people, New York, eastern industrialists, Pittsburgh people, the whole West Coast going in the other direction, up in the northwest. It was just a struggle from start to finish, and that’s what I’m most proud of, that we actually did that and put it through.”

Child receiving shoes purchased by Marshall Plan funding

It wasn’t just money that was given to Europe; the Marshall Plan created a lasting partnership between Europe and the United States that involved economic and technical assistance. The ERP addressed each of the obstacles to postwar recovery. Rather than focusing on the destruction caused by war, the Marshall Plan looked to future possibilities. It emphasized modernizing European industrial and business practices using high-efficiency American models, reducing artificial trade barriers, and instilling a sense of hope and self-reliance. Building materials, furnaces, cars, food, bicycles and much more were sent using this label on all aid packages. Dry foods were shipped in burlap sacks such as this one, which was used to transport rice to Greece.

The label used for products funded by the Marshall Plan featured on a rice sack

Notice the iconic shield symbol with the image of a handshake, signifying the partnership between Europe and the United States. The shield’s red, white and blue colors and Stars and Stripes pull from the American flag. When combined on a shield, which represents strength, this imagery makes a strong statement to its war-torn beneficiaries that the United States was there to help. Below the shield you can see M.O.C., which stands for the Maritime Overseas Corporation, a shipping company that was instrumental in sending aid to Europe. This 100-pound bag of California rice, along with thousands like it, was shipped to the port city of Piraeus just outside of Athens.

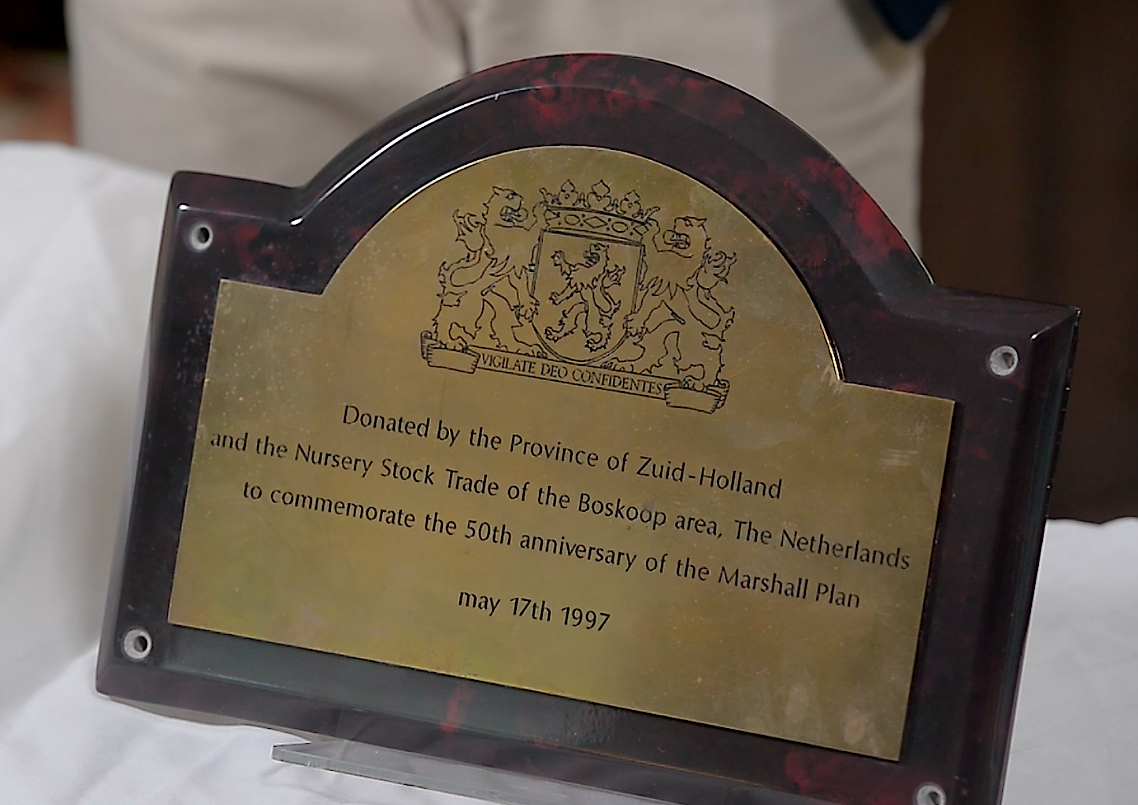

Plaque donated to the George C. Marshall International Center by the Province of South Holland

The Marshall Plan was so significant that the world celebrated its 50th anniversary in 1997. The main feature was the main celebration on May 28, when President Bill Clinton and other world leaders gathered in The Hague, Netherlands, to honor General Marshall for his work to rebuild postwar Europe. This plaque was donated to the George C. Marshall International Center by the Province of South Holland in the Netherlands. It was presented by representatives of the Nursery Stock Trade the same day that a commemorative white oak tree was planted in front of Dodona Manor to honor the Marshall Plan.

President Bill Clinton commemorating Marshall at the fiftieth anniversary celebration of the Marshall Plan

The Netherlands received $1.1 billion in Marshall Plan aid. At $109 per capita, the Netherlands was one of the countries in Western Europe that received the most funds from the plan. The largest contributions for industry went to food production, textiles and the aviation industry. Steel producers could purchase specialized equipment, and the cement industry could expand to keep up with increasing building demands. In fact, a total of half a million dollars was invested in cement. Houses were reconstructed, farms were plowed with cutting-edge equipment, and tourism was stimulated. A large number of experienced American businessmen, engineers, architects, and industrialists provided technical assistance to help The Netherlands back on its feet. I think the Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs put it best when he said, “Churchill’s words won the war, Marshall’s words won the peace.”

I hope you enjoyed this episode of “Now and Then at Dodona Manor” and that you take away the kind of leadership qualities that define an exceptional leader. George Marshall has often been called the “Last Great American,” but I believe that if more of us emulate his integrity and dedication to his countrymen, it will benefit us all.