Secretary of Defense Flag

The Episode

We’re back with another episode of “Now & Then at Dodona Manor.” This one is special because I’m going to show you one of my favorite objects in our collection. Before we get to that, let’s talk about why the object is so significant. It has to do with General Marshall’s last government position – secretary of defense. The Korean War began when communist North Korea invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950, and a United Nations resolution on June 27 called for an armed response.

Truman visiting Dodona Manor with his daughter, Margaret

Questions for Thought and Discussion

Seeking advice on the U.S. response, President Harry Truman invited Marshall to lunch with him and General Dwight Eisenhower in Washington, DC, on July 5. Truman couldn’t wait, however, and he awoke Marshall on July 4, giving him an hour’s notice that he was coming to Dodona Manor that morning. Truman’s daughter Margaret drove him to Leesburg, and they arrived around 9:30 and left at noon. In addition to hearing Marshall’s views on the Korean conflict, Truman wanted to see if Marshall was willing to take on yet another position as public servant: secretary of defense.

In his diary, Truman recounted his discussions with Marshall about China, Formosa, Japan, MacArthur, Chiang Kai-shek and the Defense Department, describing it as “a most interesting morning.” Marshall implied in a letter to a friend that the president had talked to him about the position: “Most confidentially, I have been trembling on the edge of being called again into public service in this crisis, but I hope to get by unmolested, but when the President motors down and sits under our oaks and tells me of his difficulties, he has me at a disadvantage.”

The Marshalls later vacationed at Huron Mountain resort in Michigan in August when Marshall got a phone call. It was President Truman asking Marshall to see him when he returned to Washington, DC. Marshall was not surprised when Truman asked him to succeed Louis Johnson as secretary of defense. Upon learning of his new appointment, Marshall told a friend that Katherine was “game” about his new position, but that she was “profoundly depressed” when the press incorrectly reported that she had been “delighted.”

Rosenberg, Marshall, and Lovett

The appointment required a congressional waiver because the National Security Act of 1947 prohibited a military officer from serving in the post within 10 years of being on active duty. Marshall was the first person to be granted such a waiver, and in 2017, General James Mattis became the second. Marshall’s main role as secretary of defense was to restore confidence and morale to the Defense Department while rebuilding the armed forces following their post-World War II demobilization. Marshall worked to provide more manpower to meet the demands of the Korean War and the Cold War in Europe. To achieve his goals, Marshall hired a new leadership team, including Robert A. Lovett as his deputy and Anna M. Rosenberg, former head of the War Manpower Commission, as assistant secretary of defense for manpower. He also worked to rebuild the relationship between the Defense and State departments and the relationship between the Secretary of Defense and the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Marshall participated in conversations that authorized General Douglas MacArthur, commander of United Nations forces, to conduct operations in North Korea. A classified document from Marshall to MacArthur on Sept. 29, 1950, made the Truman administration’s commitment clear. Marshall and the Joint Chiefs of Staff were generally supportive of MacArthur because they believed that field commanders should be able to exercise their judgment in accomplishing the intent of their superiors. Later, however, they cautioned MacArthur that U.N. forces must not cross the Yalu River into China because they were fearful that it might bring China and the Soviet Union into the conflict and start another world war. They also ordered him to refrain from bringing Nationalist China into the war.

Douglas MacArthur

Following Chinese military intervention in Korea during late November 1950, Marshall and the Joint Chiefs of Staff sought ways to support MacArthur while avoiding all-out war with China. In the debate over what to do about China's increased involvement, Marshall opposed a ceasefire on the grounds that it would make the U.S. look weak in China's eyes, leading to demands for future concessions. In addition, Marshall argued that the U.S. was obliged to honor its commitment to assist South Korea. When some in Congress favored expanding the war in Korea and confronting China, Marshall argued against it, continuing instead to stress the importance of containing the Soviet Union during the Cold War battle in Europe.

One of Marshall’s hardest decisions, and possibly his most controversial as defense secretary, was a result of public statements from MacArthur that contradicted the commander-in-chief’s execution of the war. On April 6, 1951, Truman met with Marshall, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Omar Bradley, Secretary of State Dean Acheson and advisor W. Averell Harriman to discuss whether MacArthur should be removed from command. Marshall, ever the conscious thinker, asked for more time to make his decision. On April 8, the Joint Chiefs of Staff told Marshall that MacArthur's relief was desirable from a “military point of view,” suggesting that “if MacArthur were not relieved, a large segment of our people would charge that civil authorities no longer controlled the military.”

Marshall, Bradley, Acheson and Harriman met with Truman again the next day. Bradley informed the president of the views of the Joint Chiefs, and Marshall added that he agreed with them. Truman wrote in his diary that “it is of unanimous opinion of all that MacArthur be relieved. All four so advise.”

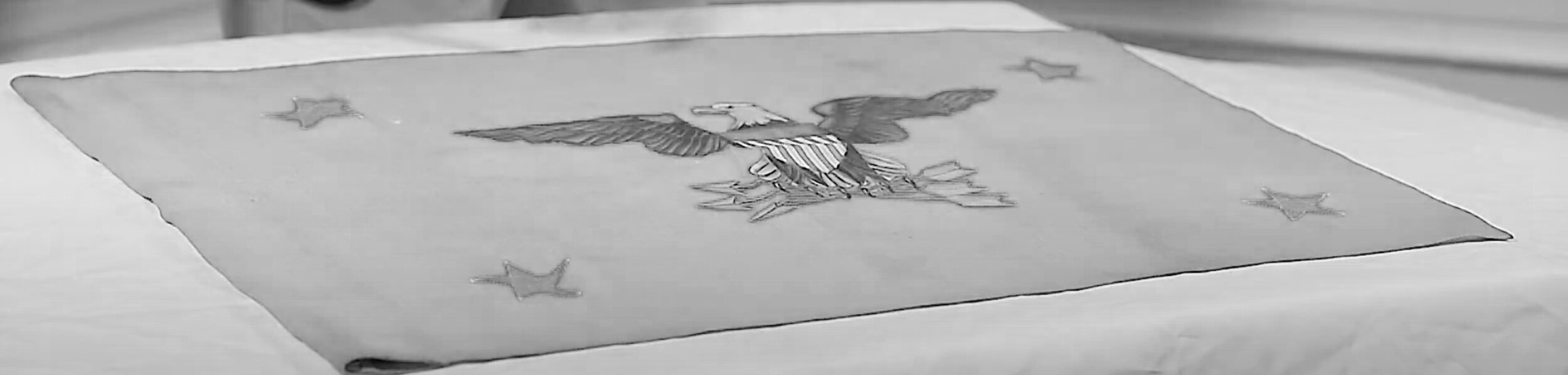

Marshall’s secretary of defense flag

President Truman relieved MacArthur of his assignment in Korea and gave the command to General Matthew Ridgway on April 11. In line with Marshall's view, MacArthur's relief was looked upon by proponents as being necessary to reassert civilian control of the military. A young Air Force sergeant, Bill Vitale, carried and delivered the order from Marshall’s office to the White House. Sgt. Vitale was only 20 years old when he was served as an Air Force enlisted administrative aide in 1948. He served under the first five secretaries of defense, including Marshall, and donated this object to us.

Sergeant William Vitale

This is the flag that flew on General Marshall’s limousine while he was defense secretary. The creation of the Department of Defense in 1947 led to the development of personal distinguishing flags. The first of these was that of the secretary of defense himself. This flag, approved by President Truman in October 1947, is “defense” blue with a bald eagle in the center and gold stars in each corner. The three arrows the eagle is clutching stands for the executive, judicial, and legislative branches of government. In the eagle’s center is the shield of the United States, signifying strength through power. Take a moment to imagine a sleek black car with a shiny chrome grill pull up to the Pentagon with this flag flapping from the front bumper. We’re lucky to have this in our collection because of Sgt. Vitale’s kind donation. At 92 years old, he still tells stories of General Marshall’s kindness and character.

On Sept. 12, 1951, Marshall’s last day as secretary of defense began quietly. Due to his declining health, Marshall knew it was time to step down. The past year had been marked by cooperation with Congress, something Marshall felt people easily lost sight of. He praised the press in the Pentagon and paid a special tribute to the defense department staff – the most efficient group that he had ever seen in time of peace. In conclusion, in his usual way, Marshall said that he could not take credit for what had been done. He said that it “now appears to be as appropriate a time as any to wind up 50 years of uninterrupted daily service to the government.” Marshall was 70 years old and finally returned to Dodona Manor to tend to his garden.

I hope you enjoyed this episode of “Now & Then” at Dodona Manor. Catch us next time when we discuss the highest honor Marshall was bestowed, two years after his retirement from public service.